Career or Children? Why Theatre Parents Feel Forced to Choose

Originally published on Playbill.com

View this story online

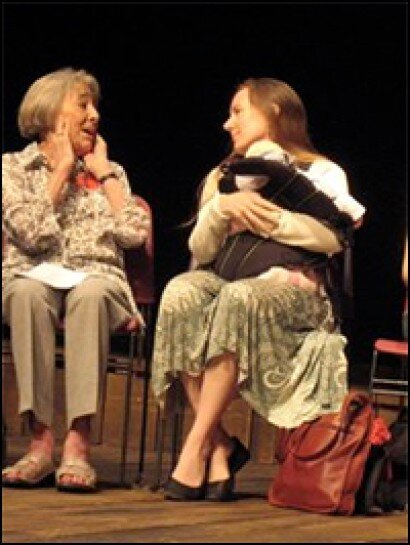

When award-winning playwright Sarah Ruhl attended the first-ever Lilly Awards ceremony, honoring the accomplishments of women in theatre, she had no idea the evening would end with her breastfeeding her daughter Hope onstage next to acclaimed composer Mary Rodgers.

“It was all like a dream to me,” Ruhl said, laughing. “I thought it would be a little cocktail reception. I had no idea there would be an audience… There I was, sitting next to Mary Rodgers and holding Hope! I thought, ‘What if Hope cries while one of these formidable women is talking?’ Then she started crying, so I started breastfeeding her onstage.”

Ruhl said she hoped that the 300 people in the audience couldn’t see her breast. But then Mary Rodgers tapped her on the arm and said, “That’s a good girl.”

The combination of motherhood and work in the theatre is nothing new for Ruhl, nor was it an option for Quiara Alegría Hudes, author of Water by the Spoonful and Elliot, A Soldiers Fuge and bookwriter for In the Heights, who went into labor during tech rehearsal for the Tony-winning musical’s Off-Broadway premiere. Hudes, who said she timed her pregnancy to coincide with following the show’s opening, described her baby’s premature labor as “a very dramatic arrival into the world.”

“We had literally just frozen the show. Press was going to start coming the next day,” Hudes said. The bookwriter had given the cast one last line change before going to dinner with her husband. During the two-block walk back to the theatre, she went into labor, and her director, Thomas Kail, took her home in a taxi.

“By the time the curtain was down that night, she was born,” Hudes said. “The timing was pretty uncanny.”

Ruhl and Hudes’ experiences reflect the unpredictable nature of the worlds of motherhood and theatre colliding, which resulted in entertaining anecdotes for the two writers. For Celia Keenan-Bolger, last seen onstage in New York in Ruhl’s play The Oldest Boy, playing a pregnant woman, her work schedule accommodated her pregnancy perfectly.

“When people say, ‘There’s never a good time,’ what they actually mean is, ‘You’ll figure it out when it happens,'” Keenan-Bolger said. “It was amazing to me how everything aligned once I was pregnant. I was able to work through my second trimester and I had my whole third trimester off, which was amazing. Those are the things that you can’t plan. That’s a part of what makes it so tricky in our business.”

With no official policy regarding parental leave in place, managing both personal and professional life in the theatre can be difficult for many in the industry, and requires extremely careful planning on the parents’ end.

“There is no federal law that requires employers to offer paid maternity or paternity leave,” Thomas Carpenter, Eastern Regional Director and General Counsel at Actors’ Equity Association, said in a statement to Playbill.com. “While the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) allows for unpaid parental leave in some cases, employees who receive paid leave usually access that through an insurance benefit or an employer policy. Equity negotiates collective bargaining agreements with employers, which may have provisions regarding maternity leave and/or disability pay, but each union agreement has its own provision, which may differ from another agreement, depending on what was negotiated.”

“NO SUCH THING AS MATERNITY LEAVE”

The lack of federal legislation requiring paid maternity leave has proven to be a challenge for parents in the theatre industry, with Ruhl describing theatre and motherhood as feeling as if they were at war.

“When I found out I was pregnant with twins, I thought I wouldn’t be able to write again… It feels like sort of an ad hoc thing: women in theatre trying to organize their lives around motherhood and theatre,” Ruhl said of navigating her work as well as parenting her three children. “For playwrights, in particular, there are no set guidelines or model or official leave. We’re all making it up as we go along.”

“There is no such thing as maternity leave in the world that we live in,” Kait Kerrigan, who is expecting her first child with her husband Nathan Tysen, said. “We own our work, which is a great thing. But we aren’t in a position when it comes to health insurance, maternity leave, bigger things like that you’re kind of just dealing. You take the time off that you need to take off, but you also don’t make money when you do that.”

Carpenter told Playbill.com that if members of Actors Equity expressed a need for maternity leave, research would be pursued. Describing the negotiation process as “member driven,” Carpenter said a great deal of outreach and surveys are executed with the members, most recently through focus groups.

“I’m not aware that anyone has brought that up as something they want the union to pursue in negotiations,” he said. “Certainly if we started hearing from members, ‘We want you to start making proposals for child care,’ we would have that conversation and go through the process of trying to negotiate.”

Newly elected Equity president Kate Shindle weighed in on the matter, as well as the expectations of working parents, saying, “I think that what’s happening is that we want to keep women working for longer, and I think one of the discouraging things is when you think women are being made to choose between career and family or being made to feel like they shouldn’t have to choose between career and family. They should be able to do everything. I don’t think that’s very realistic. To the extent that I can have conversations with people and learn more about the issue, I feel like Equity can be a part of any number of those things if it’s practical and reasonable for us to do so. And the more that we can support women being able to have families and careers — and men for that matter, because it’s not just a woman’s issue — the happier I’ll be.”

The lifestyle of a musical theatre writer contributed to the hesitation Kerrigan felt when she and her husband began discussing having a child. Listing the financial struggles and the scheduling demands, including networking while attending concerts and performances, she said, “It’s definitely something I wasn’t positive I was going to do.”

Kerrigan wasn’t alone; Hudes also felt hesitation when she learned she was pregnant. “When I was pregnant with my first child, I emailed Sarah [Ruhl], and said, ‘I don’t know how to do this,'” she recalled.

One challenge of being a parent in the theatre world is health insurance. Through Actors Equity, actors are required to have at least 12 weeks of covered employment in any 12 calendar months (accumulation period) to qualify for six months of coverage. If actors attain 20 or more weeks of covered employment in an accumulation period, they may qualify for 12 months of coverage.

The Equity website states: “Participants are evaluated for health coverage eligibility after the end of each month and there is a two-month waiting period after the 12-month accumulation period ends before coverage can begin (e.g., if you had 12 weeks of covered employment for the 12-month period ending on December 31, your coverage could begin as early as March 1 the following year).”

When preparing to give birth, Keenan-Bolger and her husband John Ellison Conlee coordinated their Actors Equity and Screen Actors Guild insurances so their child is insured until 2017. But, Keenan-Bolger admitted, she thinks about July 2016 approaching and ensuring that her coverage will continue.

Kerrigan purchased her health insurance through the partnership she formed with her writing partner Brian Lowdermilk. The plan, she said, includes an extremely high deductible of $6,000, and, during her pregnancy, she was required to undergo extra tests for which she was billed $7,900. After numerous and lengthy phone calls, Kerrigan eventually was able to resolve the bill.

The United States provides less maternity leave than any other industrialized nation. Jody Heymann, founder of the University of California Los Angeles’ World Policy Analysis Center, recently told Voice of America, “While 188 countries, that’s virtually every country, has paid maternity leave, the United States, now with Papua New Guinea, Suriname, six small South Pacific island states are the only countries without it.”

A NEED FOR CHANGE

Victoria Bailey, executive director of the Theatre Development Fund, weighed in on the financial and bureaucratic aspects of maternity leave saying, “The first leap you have to make is this is the collective responsibility. Women have to have children. Many women have to work. We just have to figure out how to do this. The solution shouldn’t be that someone goes on leave and they don’t get paid. When I say ‘maternity leave,’ the model has to be some amount of paid leave, depending on what you can pull off.”

Bailey, who has two children, gave birth to both during the summers, which was convenient for her professional schedule. She emphasized that the hours required for a career in theatre work also contribute to the logistical difficulty of raising a family. “Talk to any 20 women in the theatre, and their work schedules are completely different,” Bailey said. “Some women work at night. Some women work during the daytime. A lot of us work both. I had office work, but I also had theatre responsibilities. That whole piece was hard.”

In lieu of official maternity leave, many people combine vacation, sick and personal days in order to put together a few continuous weeks at home. But many have been aware that the status quo is in need of adjustment. While working at the Manhattan Theatre Club, Bailey said she placed calls to various theatres in the United States, inquiring about their policies with regards to family leave.

“I made a lot of calls to find what people were doing around the country, and most people weren’t doing anything,” she said. “Did they have maternity leave? Most places didn’t even have one. I think this was in the mid-80s; I don’t think the Family Medical Leave Act had been passed yet.”

“We have to figure out how to be more supportive,” she said. “Yes, this is a highly intense, highly specialized, passionate business, but there are a lot of those. You’re going to have to make a choice that says, ‘We want a diverse workforce. We want gender parity. And part of hiring women, who bring all sorts of skills to the game, is that they may go away and have children.’… It’s hard to focus on the HR issues. It’s hard to focus on how little we take care of each other. I think every generation has to push that envelope a little… Part of what helps is for people to be aware of the facts and that there are places that are making it work and are not going out of business.”

“IT’S HARD FOR KIDS TO ADJUST”

For those onstage, as well as behind the scenes of Broadway, being a working parent also provides is own unique challenges.

Kerry Butler had already starred in numerous stage works in New York when she and her husband adopted a girl from Ethiopia. Butler said the working hours of an actor are easier to manage when taking care of infants, because she would have time to spend with her adopted daughter during the day. But being away at night was hard, Butler said.

“I’d wanted her for so long, and then to not be there… When she’d wake up in the middle of the night, she didn’t want me!” Butler said. “She’d want my husband. I’d be crying.” Butler’s daughter, who is now nine years old, was 18 months old when the Tony-nominated actress starred in Xanadu, and Butler hired a nanny to help with childcare. But, she said, she was determined to spend more time with her child than her nanny did.

“I would always say I didn’t adopt a baby to have a nanny take care of her,” Butler said. “I struggled more than I do now. But I would count up the hours that my nanny was spending with her to make sure I was spending more time with her than she was. I’m a little obsessive.”

Arranging time with children is a challenge for Gavin Lee, who is currently starring as Thénardier in Les Miserables and who lives in New Jersey, with a 90-minute commute to and from the theatre each day. The musical runs more than two hours, and Lee gets home around 1 AM and gets up around 7 AM every day. Relying on very little sleep in order to spend time with his two children, ages two and four, in the mornings, Lee also utilizes FaceTime between performances on the weekends.

“I FaceTimed with my kid yesterday because I had a matinee, and my two-year-old boy was just confused,” Lee recalled. “He could hear my voice, but I look so grotesque as Thernardeier, with a horrible gray, long, scabby wig and horrible makeup and blacked-out teeth. He only lasted a minute before he wandered off and started playing on his own — ‘Daddy looks really weird.'”

“It’s hard for kids to adjust to their parents being actors. The timetable is constantly changing,” Lee said of his schedule. “There’s no consistency there for kids of actors… It’s hard, but it’s worth it, and you want to do it. I don’t want to just lie in bed. You’ve got to keep fit and eat healthy. It’s very hard, but it’s doable.”

“WE PUT IT OFF FOR AS LONG AS WE CAN”

While parental leave affects both men and women in the industry, in some ways its impact is more female-oriented, according to Julia Jordan — namely the lack of child care available for participants of writing workshops. Jordan, a playwright and one of the founders of the Lilly Awards, is working to instigate change in that area. Explaining that many of the workshops require writers to leave their hometowns for several weeks, Jordan detailed that the majority of the workshops do not provide any childcare, nor do they provide housing that a family could live in together if the parents provided their own childcare.

“Some people who are childless look at me like I’m crazy,” Jordan said of the conversations she has begun about the subject. “‘Why would any money be devoted to your childcare when it’s your choice to have a child?’ I think it’s so backwards. It’s just wrong.

“I guess at the crux of our careers we’re supposed to stop?” she continued. “It’s right when you become an adult, when you hit your stride as an adult writer, that most of us get pregnant. We put it off as long as we can.”

Jordan stressed that steps to make writing retreats more family friendly are simple, beginning with providing a list of reputable babysitting services and local day camps to writers with children. She explained that the cost of a 24/7 babysitter, as well as housing for the babysitter, result in the situation being extremely expensive.

She went on to say that the location of the writers’ retreats, which are usually in rural environments, provide a great location for children and, if actors, directors and staff all brought their families, a wonderful experience could be had by all.

“Right now a lot of places consider themselves family friendly if they allow you to bring your children,” Jordan said. “When they say ‘allow you,’ that means it’s entirely on you to find it. Right now it’s really just available to people who are wealthy.”

In an attempt to change the norm with regard to childcare and summer retreats, the Lilly Awards are funding their own retreat that does include counselors for children at Space on Ryder Farm in Brewster, NY. The children attend day camp five hours a day, while the writers work. The attending writers are Nina Hellman, Laura Marks, Stefanie Zadravec, Brooke Berman, Pia Scala-Zankel as well as fathers/actors Jeremy Shamos and Ken Marks.

“We plan to make this retreat an annual event and hope that others will see it as a model and a challenge to bring their theatres and organizations out of the past and into the reality of the present,” Jordan told Playbill.com. “The idea that artists must be completely removed from their families in order to create is one that was formed when male artists were the only artists considered, and were far less involved in the upbringing of their children. Feminism changed that. Men are no longer as estranged from their children as they once were. Women, however, are still the primary caretakers in most American families. Mothers do not want or need to be fully removed from their parental responsibilities in order to create theatre. And often they simply cannot leave their children behind for economic reasons. And so they opt out or simply do not apply for opportunities, especially those in the summer, that give the childless (or those with a spouse who assumes the primary caretaker role) crucial development of their work, relationships with collaborators and visibility.

“There are a lot of reasons we don’t have parity in the American theatre, and it’s not all bias. It’s culture. Systemic bias. And this is a big one. Lillian Hellman didn’t have kids,” she said. “You just didn’t participate. You were a raiser of the society and you were a director of the society, and you had to chose. And it’s just a completely bad idea.”

The inability to attend writing retreats carries a long-term impact on the life of a work, Jordan said, adding that almost every one of her plays and musicals went through some form of summer development.

“When you have to say no to those things, your plays don’t get seen,” she said. “If you’re saying no, you’re taking yourself off the map and you’re taking that play that would have had a big showcase and keeping it in your desk. They don’t get the same kind of visibility, you don’t make contacts with the talent. It’s also a way for women’s plays to have a better shot of being seen and appreciated if they’re actually experienced rather than read on the page.”

“It seems to me that it’s society’s responsibility to pitch in when we’re taking all this time and effort out of our own lives to do it for everyone. If society caught up with the times and supported what they’re asking of us — they’re asking us to produce on two levels. They have to put in their bit, I think. The work we do, raising those kids, benefits everyone. There’s no support. I feel like we all agree the societal contract, we all pay for public schools — and then we get penalized for doing it… It’s like the world was set up some time ago with this other idea — which is obsolete, outdated and wrong in the first place – that the world revolves around single people who are childless. And it’s just not true.”

One family-friendly summer venue is the Williamstown Theatre Festival, where artistic director Mandy Greenfield, the mother of a seven-year-old and a four-year-old, said her children are adapting to the new venue better than she is. Williamstown Theatre Festival is located near numerous day camps, many of which have hosted the children of working artists throughout the summer for years.

“There’s a whole community of caregivers who are ready, willing and able to be recruited for odd hours when the actors need daycare, and they’re very accustomed to that,” Greenfield said. “We work very closely with the artists to make sure that when they bring their families here, they have these resources at their fingertips.”

Another aspect of Williamstown Theatre Festival that assists with working parents is the Guild, a volunteer organization of more than 60 members that works to foster a close relationship between the Williamstown community and the members of the Festival by providing company meals, connecting artists with local resources and providing assistance to the artists, staff and families. Said to have been started in 1955 by the wives of the founding Trustees of the Festival, the Guild provides strollers and toys to children. “Our Guild will say, ‘Tell us what you need, and we’ll provide it,'” Greenfield said.

“THERE’S A HUGE FEAR BEHIND ASKING”

Asking for what they need, whether it’s child care, family accommodations or just a stroller, is something many women have said needs to happen more in order for institutional shifts in the system to take place.

“There’s a huge fear behind asking,” Bailey said. “If you go beyond the maternity leave issue to how we accommodate people with children, you have to have a series of realistic expectations, and I think you have to have real straightforward conversations about what’s expected and what’s not. What are the expectations of this job, and what constitutes beyond the norm?”

“There’s also a supply and demand element here,” Hudes added. “If, all of a sudden, there’s a capacity issue that’s stopping [producers] from getting their hands on the plays they’re passionate about, they want to deal with those capacity issues. There’s a supply and demand element there that I think is helpful for us…I think there’s a critical mass of women, parent-age, that are having much more success. I’m talking about a critical mass of people at a certain age that have some negotiating power and aren’t afraid to use it. Having industry leaders like Lynn Nottage and Sarah Ruhl saying, ‘We have enough power to tell a theatre these are the things we need,’ really does clear a path for those who follow.”

“I think in a much broader sense, one of the things that is really hard is advocating for yourself, and that you have to advocate for yourself so strongly,” Kerrigan added. The decision of if or when to return to work after having children is another challenge unique to members of the theatre industry, where actors, directors and writers’ professional schedules are dictated by productions rather than freelance or open-ended employment by companies.

“In a nice way, some people said to me, ‘You might not want to go back to work,’ but that would require a complete change in my personality,” Celia Keenan-Bolger said. “I didn’t know until I had the baby. I’m absolutely going to want to work again and sooner rather than later. Nobody said that to my husband.

“What’s amazing about being an actor is usually you feel beholden to the industry,” she continued. “You have control over very little. Having a baby was a time when I get to be the boss of when I want to go back to work. I feel like that’s a luxury that most women don’t have, and I’m super grateful for that. Before I had the baby, I didn’t know if I was going to want to take a break for a couple of years or a couple of weeks. It was amazing to not have a plan in place about that.”

Kerrigan, who shared that she had maintained a very narrow focus on her career for much of her adulthood, said, “I definitely have personally struggled with a feeling of guilt about making any decisions that are not career based and choosing something that’s not the most helpful for my career, but the most helpful thing for my personal life and the child that’s coming. That’s a strange feeling. I know it’s irrational. It comes from being a little bit of a workaholic and someone who’s put my career before anything else for the past 10-12 years. So now trying to make that shift for myself has been hard.”

A PLACE OF THEIR OWN

Despite the challenges of being a working parent, the theatre community is remarkably family-friendly in many ways, Lee said, recalling when he was starring in Mary Poppins, that the crew would bring their children to the theatre between performances on Saturday. “With the opening set of Poppins, they used to let the toddlers climb up and down the chimneys and they’d fill the stage with dry ice. You’d have these two and three-year olds running around and jumping into the dry ice. They’d have the best time.”

One way in which Butler ensures she will be able to spend time with her children while working is to have written into her contracts that her children can visit her backstage. During Xanadu, Tony Roberts would perform exercises with her daughter, and when Butler was performing in The Best Man, her daughter would make cookies and bring them to the cast of the show, knocking on Angela Lansbury’s door and delivering chocolate-chip cookies to the Tony-winning actress.

“They love being around the cast members, because they’re larger than life,” Butler said.

“Sometimes I think theatre is an incredible job for a parent — a father or mother — because it’s flexible,” Ruhl said. “You can bring your kids to rehearsal. Kids enjoy watching theatre, and people in theatre generally love kids because they tend to be playful people who love life. I do think the culture of theatre is changing, where I’m seeing more openness about the permeability between the rehearsal room for fathers and mothers. And I hear more talk about it from the artistic directors and designers.”

Reflecting on the hectic schedule of two-show days and five-performance weekends, Lee shared an idea of a communal space for children of actors in Manhattan, allowing parents to spend a few hours with them between performances on the weekends.

“I’ve often discussed with people who have kids, wouldn’t it be great if all the producers could get together and just find space for those five-show weekends — kind of like a nursery play space that, if you have your Equity card, could be like child care? Wouldn’t it be great if all the Broadway kids could get together and play, so the parents who are in the shows could come between shows and see them. It would be nice if there was this communal place right in the heart of Theatre District that we could bring our kids to and look forward to dashing there and having a couple of hours with our kids on Saturdays and Sundays.”

Lee’s idea actually had been proposed and researched in 2008 by The Actors Fund, the nonprofit human service organization that offers social services and emergency financial assistance, as well as educational, vocational and health insurance resources to members of the theatrical community. A parents committee was created to conduct a survey about childcare needs in the industry. With more than 600 people surveyed, approximately 60 percent said they had between one and four children, and 40 percent didn’t have children but thought they might in the future. More than half — 62 percent — said that childcare issues had caused them to miss work or auditions. The responders to the survey shared hope for a day care center in the Times Square area where they could drop off their children for a few hours at a time in order to attend an audition, rehearsal or other work-related commitment.

“Unfortunately the model of childcare we have here in the United State doesn’t match that,” Tamar Shapiro, national director of social services at the Actors Fund said. “It’s very difficult to find that where you can drop someone off for a limited period of time and pay as you go. And it’s also very difficult to find late-evening coverage.”

She went on to explain that various childcare centers had been investigated to see if they could be utilized to meet the actors’ needs, but the models that were in existence could not be restructured due to insurance and financial matters, adding, “The way that we’re structured as a country doesn’t really work that way with child care. Because of the flexibility that people in this business need, because of the changing hours that people work and the changing schedules they have, and the fact that they’re not traditionally business hours it makes it that much more challenging to find a larger system that will accommodate that.”

Along with financial assistance and counseling, the Actors Fund offers a resource directory for members of the community to assist with managing work-life balance. And while the theatre community is supportive of working parents, Kerrigan said, she believes a move to a more communal aspect of childcare is a necessary shift for present-day culture.

“There’s nothing that’s a given about the way that we handle childcare,” Kerrigan said. “Everything is: You deal with it yourself or we all have to invent a new way of dealing with it as a community. And both of those things are hard. Acting like it’s completely and entirely your responsibility to figure that out on your own and in private and not talk about it feels hard. And on the other side, having there be a community-wide change in the way we deal with it is a monumental task to undertake.”

“I think it’s not mindful,” Greenfield said of the current status quo. “I think probably there’s been a little more attention and mindfulness in other industries, and I think we’re just arriving at that mindfulness. But I think there’s been thought and strategy around these questions in some of these industries, and we’re just getting to it now. It’s well within our industry’s grasp to evolve.”

“I do think you could argue it’s been a boy’s club in certain circles in the theatre for a long time,” Ruhl said. “And I think the literature of the theatre itself is about families, is about children, is about all of those profound relationships…The more women you have working — not just women, and the more men you have who are really involved in their children’s lives and who are in the theatre — and the more parents you have writing plays, the more it will be part of the general consciousness.”

Ruhl recalled a dinner party at the home of Bernard Gersten, the former executive producer of Lincoln Center Theater, when her play The Clean House was in rehearsals. Thinking it was an informal dinner, she brought her son William with her. Upon arrival, she realized it was a formal catered affair, with John Guare and Tom Stoppard in attendance. When Ruhl had to breastfeed her son, Stoppard said, “Cheers to the only person here who’s working!’

“For other writers and theatre artists who are considering having children, it can be a really wonderful and generous way to have kids,” Ruhl said. “It’s a time-honored tradition. And I don’t think it’s anything to fear. I think there are more and more of us.”