Joan of Arc: Into the Fire

Originally published on Paste Magazine

View this story online

Before Joan of Arc: Into the Fire begins at the Public Theater, the words, “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted” are projected onto the curtain. While the relevance of a courageous woman defying the orders of a patriarchal society is certainly applicable to present-day culture, it is far from the most relevant aspect about this disappointingly misguided musical in performances at the Public Theater. Rather, what Joan of Arc: Into the Fire presents is a portrait of opportunistic men profiting off of hard work completed by a woman, and the woman being permitted no reaction at all.

Frustrating patriarchal themes are to be expected in a musical about Joan of Arc. After all, it chronicles the story of a woman who defied convention, assumed a man’s role in society and eventually was burned at the stake for her actions. But this musical, whose book, music and lyrics were all written by David Byrne, presents no response or analysis to the injustice Joan suffers. It simply presents it onstage without commentary, analysis or even irony.

Reaction or feminist exploration are not the only crucial elements missing from this Joan of Arc, which includes little to no conflict to drive its lagging narrative, even in a brief 100-minute performance. Directed by Alex Timbers and presented as a bio-musical reminiscent of Jesus Christ Superstar, it introduces ten male actors, asking, “What does it cost to be free?... What can one person do?” Then Joan, played by Jo Lampert, takes the stage, urging the men, “Have faith. Be strong,” a refrain that persists throughout the musical.

Wardrobed in a dress and adorned with long braids, Joan recalls her childhood and when she experienced a vision from God instructing her to lead France’s army. During this vision that the fact this musical was written and led by a male team was first apparent, as, apparently, all it took to convince her to abandon her life and lead an army was for God to tell her, “You are so beautiful.” After a brief exchange with Captain Baudricourt (Michael James Shaw), who was experiencing a crisis of doubt about battle, Joan manages to reassure him that she will lead him to greatness, saying, “It’s you that we need. I’ll give you strength. I’ll keep you strong. This is a prayer for everyone.”

Joan’s first encounter with the dauphin (Kyle Selig) provides even more appalling sexism, as she is subjected to an examination to confirm if she is, in fact, a virgin, as it dictated only a virgin can speak to God. Joan appears to have to no problem with this requirement and willingly undergoes the examination. An historic fact, yes, but did this scene really have to be staged with a group of men standing behind her, smiling approvingly as they sing, “Intact and whole/Pristine and pure”? If this was intended as a commentary on the sexism of the time, or a mirror of how female purity is still fetishized today, it failed to communicate.

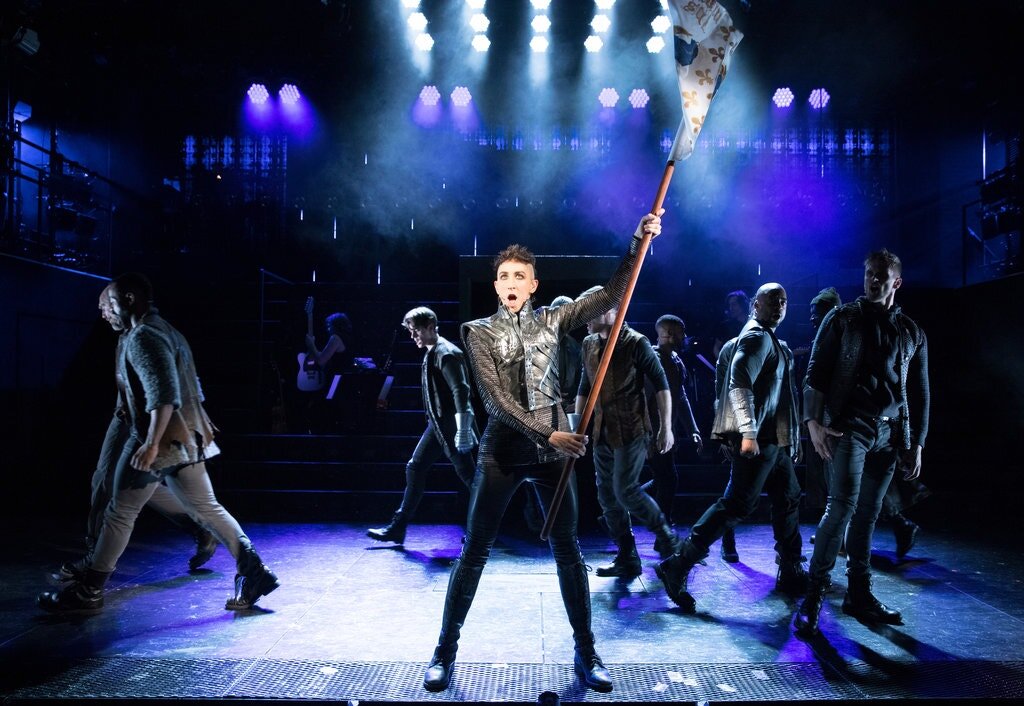

The musical follows Joan through training for battle-apparently, none of the male soldiers had any problem with her joining them-losing her braids and donning men’s clothing while singing about being neither a boy nor a girl before leading the men through victories, adorned in Clint Ramos’ stylized costumes. Staged with much feet-stomping movement on Christopher Barreca’s decidedly modern set and Justin Townsend’s lighting, feature strobe lights and stage fog, the scenes are less than gripping due to Steven Hoggett’s mechanic choreography. Joan is attacked verbally in battle by her opponents, called a “whore” and a “slut” and told she’s leading an army of “pimps,” but she is seemingly deaf to these sexist slurs, simply telling her men, “Have faith. Be strong.”

After a number of victories, of which the audience is informed through Darrel Maloney’s projections, Joan’s devotion to fulfilling God’s plans changes from being an asset to being a liability. Because of her victories, the Dauphin is crowned the King and Joan is immediately told, “Your work is done” as the King begins parroting the exact phrase she had been saying: “I am God’s messenger.” Lampert’s distraught expression as she slowly walks away from the King while hearing him steal her words is all too familiar to any woman who has witnessed her own idea being spoken and warmly received by men.

But Joan never expresses frustration or anger about any of her experiences. Despite a tireless performance by Lampert, the title character disappoints because she is written as simply one-note with little to no conflict: she believed in God and what God was telling her to do. And this belief was unwavering, despite the doubt expressed by her fellow Frenchmen as well as the English who capture her. “Persistent” could also be used to describe the melodies, which, unlike the widely varied and diverse score of Byrne’s previous musical Here Lies Love, is repetitive and eventually monotonous. Many of Joan’s songs seem to consist only of her belting long vowels to Heaven.

Her faith persists even she is captured and subjected to another examination to confirm her virginity (after which, one man says to another, right in front of her), “Sir, she is a good girl. It is intact” (at which point this critic shuddered in her seat and longed for the phrase “good girl” to be banished from all conversations regarding women’s sexuality). Joan is then at the mercy of Bishop Cauchon (Sean Allan Krill) who asks, “What gives her the right to take another life?... determine wrong from right?”-even though at that exact moment he was doing that exact thing as well as reflecting on how his treatment of Joan would impact his own reputation and career.

The hypocrisy is presented bluntly throughout the musical but never commented on by any character, nor even given a winking reference in the book or lyrics. In fact, one of the only moments when the musical does attempt to present something humorously is the song, “Many Parts, One Body,” in which a priest played by Rodrick Covington sings a calypso-style number to Joan about the physical torture she could face if she does not cooperate. Jarringly out of tune with the rest of the show, this number is horrifyingly unsettling and not at all funny..

Joan of Arc concludes with an obvious attempt at positive thinking, with Joan’s mother (played by Mare Winningham) asking for a posthumous retrial of her daughter, urging the bishops and priests to “send her to Heaven.” It’s a fitting conclusion for a show about patriarchal power structure. Even though Joan made her own decisions, including the recanting of her confession that led to her death, of course, her place in the afterlife is a choice left to a group of men.