‘Blonde’: Is the New Marilyn Monroe Movie an Antiabortion Fever Dream?

Originally published on VanityFair.com

Read this story online

Joyce Carol Oates has described Blonde, the film based on her novel of the same name, as “surprisingly feminist.” The author of 58 novels, Oates devoted more than 700 pages to her prodigious fictionalization of Marilyn Monroe’s life, beginning with the young girl Norma Jeane and ending as the tragic Hollywood icon. A finalist for the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize, Blonde is widely viewed as the prolific writer’s masterpiece.

Drawn from the widely known facts of Monroe’s life—her famous film roles, her infamous relationships, and her mysterious death—Oates’s novel is a shocking, horrifying, and engrossing portrait of the woman behind the glossy red-lipped smile. The film by writer-director Andrew Dominik is equally shocking and horrifying, but in different and wildly unexpected ways. It is surprising, but it is not feminist. By adapting Oates’s novel to the screen, he has produced an exploitative film with an underlying anti-choice agenda. Rather than honor the victim of patriarchy, the patriarchy of the film has overwhelmed and almost erased her.

Oates has said the novel was inspired after she saw a photograph of Marilyn Monroe when she was 15 years old and still known as Norma Jeane Baker. Recalling the triumphant beauty queen’s youth and innocence, Oates told her own biographer, Greg Johnson, “I felt an immediate sense of something like recognition; this young, hopefully smiling girl, so very American, reminded me powerfully of girls of my childhood, some of them from broken homes.”

The loss of that innocence infuses the novel, which chronicles Norma Jeane’s rise to fame through a studio system in which she was mistreated and molded to please the male gaze. Oates narrates a lifetime tormented by parental neglect, sexual assault, and domestic violence in an unforgiving portrait of the damage it wrought on the hopeful young woman. It’s not an easy read—chaotic stream-of-consciousness monologues, lacking punctuation, fill pages at a time, and Oates composes fictional diary entries that list the horrors Monroe endured and the destructive ways in which she coped with them. The book is engrossing and enlightening—and absolutely terrifying.

The feminist credentials of Blonde, the novel, are questionable. Oates does offer a brutal look at the male-dominated establishment of Hollywood and its inhumane treatment of women, presenting Monroe as an intellectual reduced to a dumb blonde by the men around her. Her Monroe writes poetry, reads Stanislavski and Freud, and attends night classes in disguise. But Oates also ignores the real Monroe’s accomplishments. Instead, she is a victim, with little agency or authority. Whether Oates honors the actor by depicting her as one is subject to interpretation.

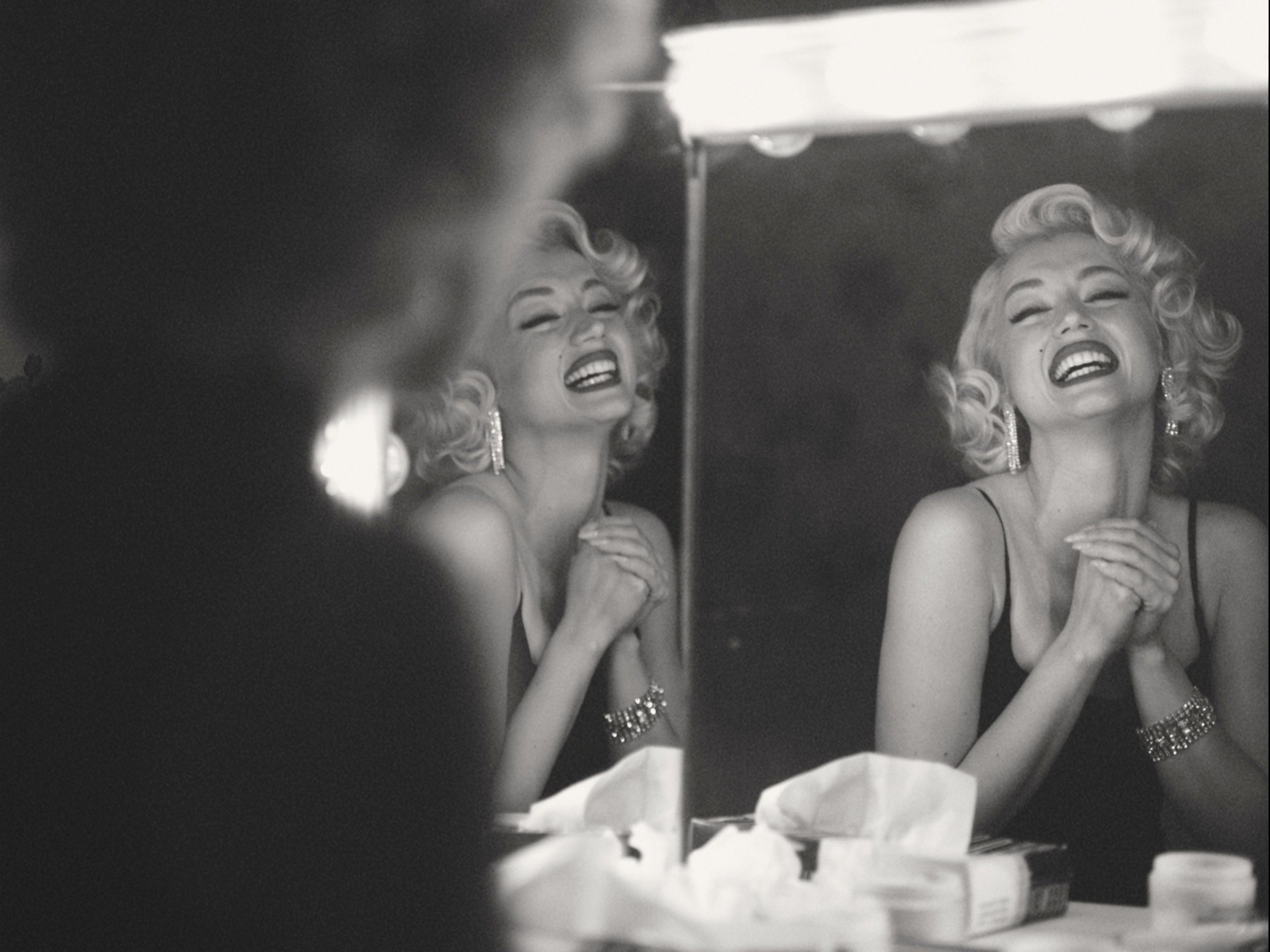

Following a ponderously faithful made-for-TV adaptation in 2001, some questioned whether Blonde could ever be successfully translated to the screen. Twenty-one years later, we appear to have our answer. Despite a moving performance by Ana de Armas as Marilyn, Dominik’s film proves that what established the book as simultaneously shocking and thrilling is instead vulgar and exploitative on film.

The word abortion is never spoken in Blonde, but it hovers over almost every scene of the film’s two hours and 46 minutes, adding even more weight to a movie already burdened with brutal illustrations of painful subjects. Mental illness, addiction, and suicide are just a few tragedies the film plunges into, but its portrayal of abortions is especially heavy-handed and painful to witness following the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade.

Monroe has been rumored to have had several abortions in real life, but only two are included in the film, their depictions offering a strong argument to categorize Blonde as a horror movie. Subtlety is hardly a strength of Dominik’s. Blonde includes several close-up shots of a fetus as it develops in Marilyn’s stomach, one of which is pointedly shown while she calls the studio to arrange her abortion. On the way to the procedure, Marilyn, somberly clad in a black dress, begs her driver (in a car strongly resembling a funeral hearse) to turn around after seeing a stop sign. Her pleas continue on the operating table but are ignored by the doctors until an injection lulls her into a “twilight sleep.” What follows is a close-up of her cervix before she dreams of fleeing from the doctors and saving a baby from danger as the sweetly crooning song “Bye, Bye, Baby” plays.

That the Marilyn of the movie regrets this decision is undeniable. She is shown as haunted by her abortion, paralyzed in her dressing room and unable to perform. While surrounded by thunderous applause at the premiere of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, she wipes tears from her eyes and whispers to herself, “For this you killed your baby.”

Blonde’s Marilyn is seen as desperately longing to lose herself in the identity of a mother, elated when she becomes pregnant in her third marriage and responding to her husband’s jokes about food cravings with, “Baby makes his wishes known. Norma’s just the vessel!” While discussing his wife, The Playwright (Oates’s name for Arthur Miller) remarks, “Pregnancy agrees with her…. She says, ‘This is how it’s supposed to be, I guess.’” Dominik’s most shocking choice, however, is seen when Marilyn hears the fetus (again, shown developing in her body) plaintively asking her, “You won’t hurt me this time, will you?” After she protests that she didn’t mean to end her first pregnancy, the fetus tells her, “Yes, you meant to. It was your decision.” Presented as its own being, with its own voice, the fetus is clearly shown to be a life, independent of its mother, before it is born.

The hell that Blonde’s Marilyn puts herself through is painful to watch, due to de Armas’s remarkably raw performance. She tortures herself after she miscarries, losing herself in drugs and alcohol. While performing a scene from Some Like It Hot, her character is accused of being “careless,” and the screen is filled with images of her fetus dying when she miscarried. De Armas plays Marilyn as a scared girl, tremulously quivering in fear as she seeks approval from every (male) figure in her life. Her breathy voice and wide eyes only enhance her youthful appearance. During scenes in which everyone is clothed in dark colors, she is dressed in shimmering white.

Oates created a character desperate to be a mother and tormented by her inability. Dominik and de Armas’s Marilyn is a faithful adaptation of Oates’s, but that devotion does not translate into a successfully entertaining film. Instead, the horrifying images that illustrate the abortions—close-up shots of the procedure and its ongoing effects on Marilyn’s mental health—come across as promotion of an anti-choice agenda associating abortion with horrific violence and declaring it murder. Fetal personhood, the idea that life begins at conception, is an excuse for the onslaught of anti-choice legislature in America, and Dominik has directed a film in which a fetus begs the woman carrying it, “You won’t…do what you did the last time?” The theme of violence is even more heavy-handed when, the morning after Marilyn is forced into another abortion, presumably by The President, she stumbles out of bed confused and discovers the lower of half of her body soaked in blood.

It’s undeniable that Marilyn is a victim. She is remarkably sympathetic, which inspires the question of why Dominik chose to shoot the movie as he did. Why torture this Marilyn, and by way of de Armas’s compelling presence, the audience? The pain of Marilyn’s childhood and the horrors of her adulthood have been examined in countless books, movies, and podcasts. Blonde’s portrayal of her pregnancies and losses does set it apart from other content, but that status comes with a cost.

“The last few days of her life were brutal,” Oates said of Marilyn. “The real things that happened to Marilyn Monroe are much worse than anything in the movie.” Why should that be experienced again? Oates has praised Dominik and the film on Twitter, writing, “…not sure that any male director has ever achieved anything [like] this.” That may be true, but there may also be reasons why.

Blonde’s Marilyn is open and exposed. She leaves everything she has onscreen, keeping nothing for herself. The patriarchal structure of Hollywood defines her life while simultaneously violating and disrespecting it, and she is unable to fight for herself. The lack of choice in Marilyn’s life is appalling, but equally shocking is the decision to present it so bluntly to an audience still reeling from their own rights being taken away.

One of the film’s most horrifying moments depicts Marilyn, having fallen on the beach and experiencing a miscarriage, screaming for her husband to help. As he races toward her, he’s surrounded by members of the press, their cameras flashing while they photograph her pain. As Dominik condemns their exploitation of her tragedies for entertainment and profit, he should have included himself in the shot.